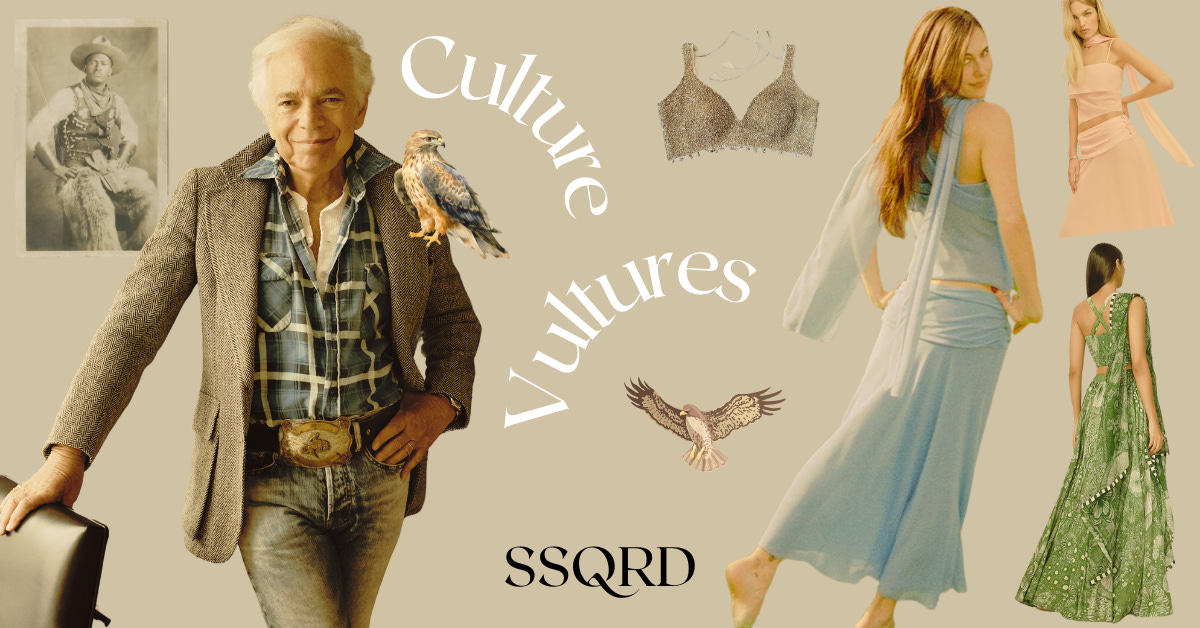

Devon Lee Carlson For Reformation and Ralph Lauren is The American Dilemma

Fashion's obsession with cultural appropriation reflects America's complicated identity. Oh and the father of American fashion is actually a Black man, not Ralph Lauren.

Devon Lee Carlson for Reformation is a tale as old as time…a white person stealing the fruits of another culture and watering it down to fit their version of a more palatable approach. After all…it's just inspiration.

The truth lies in the fact that American white people do not have an original culture. Time and time again, we witness recycled renditions of other cultures repackaged as new trends. Almost every ethnic group has been victimized by this cultural cannibalism.

Indians have had their sacred yoga and spirituality diluted into Alo Yoga and Goop cults. South Asian clothing has been rebranded as "boho chic," marketed through Coachella, Isabel Marant, and Ibiza party-girl core. Black American subcultures have been appropriated into distinct fashion trends and commodified by mega-corporations, such as LVMH, that simultaneously oppress the very communities from whom they draw inspiration. Chai and matcha from Asian cultures have been so thoroughly gentrified that they are now commonplace at distinctly American establishments like Dunkin Donuts and Starbucks. Not a single piece of clothing, item of food, or cultural tradition remains untouched by culture-hungry Americans precisely because they lack an authentic cultural identity of their own.

You might think American fashion at least is traditional: classic Ralph Lauren aesthetics, cable-knit sweaters, and denim associated with cowboy culture. But even these seemingly quintessential American aesthetics were borrowed, taken from the original cultures of others, and rebranded to create what we now mistakenly celebrate as uniquely American. Ralph Lauren is often hailed as the epitome of “traditional” American fashion. But how “traditional” is this vision? In fact, much of what we celebrate as American fashion in Lauren’s work was curated elsewhere first.

Lauren has built a fashion empire by selling an idealized American lifestyle. From the ivy-covered campuses of the Northeast to the Old West: tweed jackets, polo coats, Navajo-print sweaters, cowboy boots… in Lauren’s world they all harmonize as a single American tradition. In reality, these items were originally from immigrant laborers or regional subcultures, woven into the mainstream “American” narrative. Just as an example, the embroidered Western shirts and cowboy boots Lauren adores trace back to the influence of Mexican vaquero attire. Even the preppy staples Lauren romanticizes were adopted and adapted from British aristocratic sports and military traditions. This scenario repeats across Lauren’s product lines. His collections have featured Southwestern-patterned blankets that echo Native American designs. The Navajo and other Indigenous peoples developed those geometric blanket motifs. Working-class aviators and soldiers popularized the bomber jackets. Immigrant ranchers and black cowboys shaped Western wear on the frontiers.

When Lauren folds these pieces into his collections, the reference is usually aesthetic not attributional. A catalog description rarely credits the source culture or class beyond vague terms like “heritage” or “Western-inspired.” In marketing, the item becomes a symbol of an abstract American tradition rather than the lived tradition of a particular group.

This repackaging has real implications. While it undoubtedly introduces beautiful designs to new audiences, it also commodifies heritage in a one-sided way. The original communities seldom share in the profits or prestige. Lauren’s Navajo-inspired fashions, for instance, have drawn criticism for appropriating Indigenous patterns without permission or cultural context, effectively using sacred symbols as surface decoration. The pattern is clear: take a cultural artifact, remove its origin, and then sell it as an upscale novelty. In doing so, the artifact is rebranded as part of an amorphous American heritage to which the Ralph Lauren consumer is heir.

Meet The Real Father of American Fashion and Ralph Lauren As We Know It

Bobby Garnett was a vintage curator, often known as “Bobby from Boston” and the man who created Ralph Lauren as we know it. Over four decades, Garnett amassed a collection of 20th-century American garments. Walking into his warehouse in Lynn, Massachusetts was like stepping into a time capsule. His pieces were authentic and they exuded a character that designers like Lauren wanted to capture. As early as the 1980s, Garnett’s shows began attracting buyers from New York’s fashion scene. By the 1990s, he opened Bobby from Boston, the country’s first appointment-only vintage showroom, specifically to cater to this demand. His high-profile clientele included fashion designers like Ralph Lauren, Tommy Hilfiger, and Marc Jacobs. Lauren’s team would sift through racks, cherry-picking the most compelling items. Often, those finds would reappear on Ralph Lauren’s mood boards and eventually in upscale boutiques as new luxury garments inspired by the American past. In other words, Ralph Lauren, the supposed pioneer of American style, was inspired by Garnett to craft his next season’s look. For example, each RRL piece is designed to look like it could be vintage mid-century Americana because people like Garnett preserved the originals for Lauren to study. Garnett’s story compels us to ask: can we really call it “Lauren’s vision” when so much of it was actually discovered by someone else?

Side Eye Reformation…

This pattern of cultural appropriation persists today, illustrated by the recent controversy surrounding Devon Lee Carlson and Reformation. Carlson and Reformation faced backlash after launching a collection featuring designs explicitly inspired by traditional South Asian clothing without sufficient acknowledgment of their origins or collaboration with creators from those communities. The clothing modeled by Carlson, who is not South Asian, were presented as trendy styles without proper credit to their cultural and historical significance. This campaign further perpetuated this cycle of cultural extraction. Both Ralph Lauren’s historic use of vintage Americana and Reformation’s contemporary misstep underscore a broader truth about American cultural identity: it is often constructed not through genuine innovation but through appropriation and commodification of marginalized communities' heritage.

These examples illustrate the importance of conscious consumption, honest attribution, and respectful collaboration. They also serve as a call to action for the fashion industry to move beyond performative acknowledgment toward meaningful inclusion and transparency. It reminds us that respecting and celebrating diversity means uplifting and acknowledging the creators whose stories and identities truly enrich American culture.